The Emile Zola House – the Dreyfus Museum

In this article, I take you to Médan, a pretty little village in the west of Paris (Yvelines department), located on the banks of the Seine, very close to the village of Bures, where I live.

Why Médan, you may ask? Because Médan is really worth a visit if you like literary walks! One of our great writers of the 19th century, Emile Zola, installed his summer residence there in 1878 and remained there for 24 years until his death in 1902.

Emile Zola, the novelist

Like Victor Hugo (1802-1885), his elder, Emile Zola (1840-1902), was passionate about the social novel, a literary genre that evokes the living conditions and difficulties of the working classes and

peasants.

Like him, by his personal involvement in public affairs, he has marked history and appears as a “guardian of the people”. But while the work of Victor Hugo is part of the continuity of the romantic movement, which appeared in the 18th century, that of Emile Zola is part of naturalism, a literary movement born in the 19th century, of which he is the leader.

Naturalism is characterized by the search for reality, it wants to treat the social subject with a quasi-scientific objectivity, without empathy. Thus in his flagship work, “The Rougon-Macquart”, composed of twenty novels published between 1871 and 1893, Zola traces the natural history of a family under the Second Empire, a true study over five generations of the influence of the environment on man. And even if Victor Hugo is undoubtedly better known than Emile Zola, beyond our borders, the latter is nevertheless an essential writer of the 19th century, to be discovered or rediscovered on the occasion of a stroll in Médan.

Emile Zola and Médan

From his first literary successes, Emile Zola aspired to own, far from Paris and all its mundanities, a refuge, “a country asylum”, where he could find, in the calm of the countryside, peace, comfort, a bulwark against the relentlessness of critics, an ideal place to meditate and write.

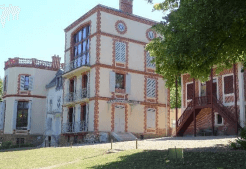

It is thus in 1878 that he buys, thanks to the royalties of his book l’Assommoir, a house in Médan, which he called, not without humor, his “rabbit hut”. With time and success, the little house will grow: it will be flanked by two towers, a square tower, called the Nana tower, and a hexagonal tower, called the Germinal tower.

As for the small garden, it will be transformed into a vast domain of several hectares, including at the time, a farm, a vegetable garden and greenhouses. It was here that Zola could indulge in the rural life he had always dreamed of. It is here that he wrote many of his masterpieces. It is also here that he organized joyous friendly meetings, “the Evenings of Medan”, in the presence of Guy de Maupassant, the Goncourt brothers and Huysmans.

As for the small garden, it will be transformed into a vast domain of several hectares, including at the time, a farm, a vegetable garden and greenhouses. It was here that Zola could indulge in the rural life he had always dreamed of. It is here that he wrote many of his masterpieces. It is also here that he organized joyous friendly meetings, “the Evenings of Medan”, in the presence of Guy de Maupassant, the Goncourt brothers and Huysmans.Finally, it was here that he led his great humanist battles that structured his work as a writer.

The Emile Zola House

To visit the Maison Emile Zola is to enter into the intimacy of the writer, strolling through typical 19th century settings, designed by himself, intact or carefully restored. It is also to discover his taste for the mixture that he drew from all the cultures of the end of the 19th century and which characterizes so well his cosmopolitan spirit.

On the first floor, the dining room with its imitation Cordoba leather walls, its stained glass windows with medieval motifs and its fleurdelisé ceiling. Next door, the kitchen, entirely covered with Delft tiles, where Alexandrine, Zola’s wife and mistress of the house, used to prepare her tasty dishes that delighted the whole household. A little further on, the salon-billard with its astonishing symbolist stained glass windows and beautiful mosaics where he liked to gather his friends. On the second floor, Zola’s bedroom; on the second, the study with its imposing Renaissance fireplace, where, methodical and faithful to his motto, “Nulla dies sine linea” (“Not a day without a line”), Zola shut himself up every morning to write. During these hours of relentless work, he tolerates no presence at his side, except that of Pinpin, his favorite Pomeranian dog.

Zola and the Dreyfus Affair

The anti-Semitic hate campaigns, increasingly virulent in France in the 1890s, prompted Zola to take a stand for the Jews. It is in this context that the Dreyfus affair, the famous story of the officer of Alsatian origin and Jewish confession, which will become a real affair of state, occurs.

Victim of a judicial frame-up in 1894, Captain Dreyfus was convicted of high treason. In 1895, he was degraded and deported to Devil’s Island in French Guiana. Very quickly, Zola was convinced of Dreyfus’ innocence. He pleaded his case in order to save him from an unjust conviction. Thus, in 1898, he published in the press his famous article, “J’accuse”, an open letter to the President of the Republic, Felix Faure. This historic appeal earned the writer the hatred and insult of his detractors. But his courageous commitment, his fight for justice and tolerance, his struggle against racism and anti-Semitism, at the risk of his freedom and his honor, won the day. In 1899, Alfred Dreyfus was pardoned and rehabilitated in 1906.

The Dreyfus Museum

To celebrate the memory and intertwined destinies of Zola and Dreyfus, the writer’s property has been home to the first museum dedicated to the Dreyfus Affair since 2021, in one of its outbuildings, “a living museum against injustice and intolerance,” in the words of one of its patrons.

It is a space conceived above all as a place of memory, to remember the lessons of the Dreyfus Affair for a long time to come, “for vigilance against oblivion, for memory against ignorance, for knowledge against recidivism”.

Throughout the discovery of this museum, which presents many little known and rarely seen documents and media (photographs, songs, light projections, brochures, posters, leaflets), the visitor is led to question the fundamental issues related to the rights of women and men, justice, tolerance and secularism.